In whatever way it makes sense that Andy Crysell is both the only person who has interviewed all members of Wu Tang Clan and founded Crowd DNA (and we think it does), his book continues this path.

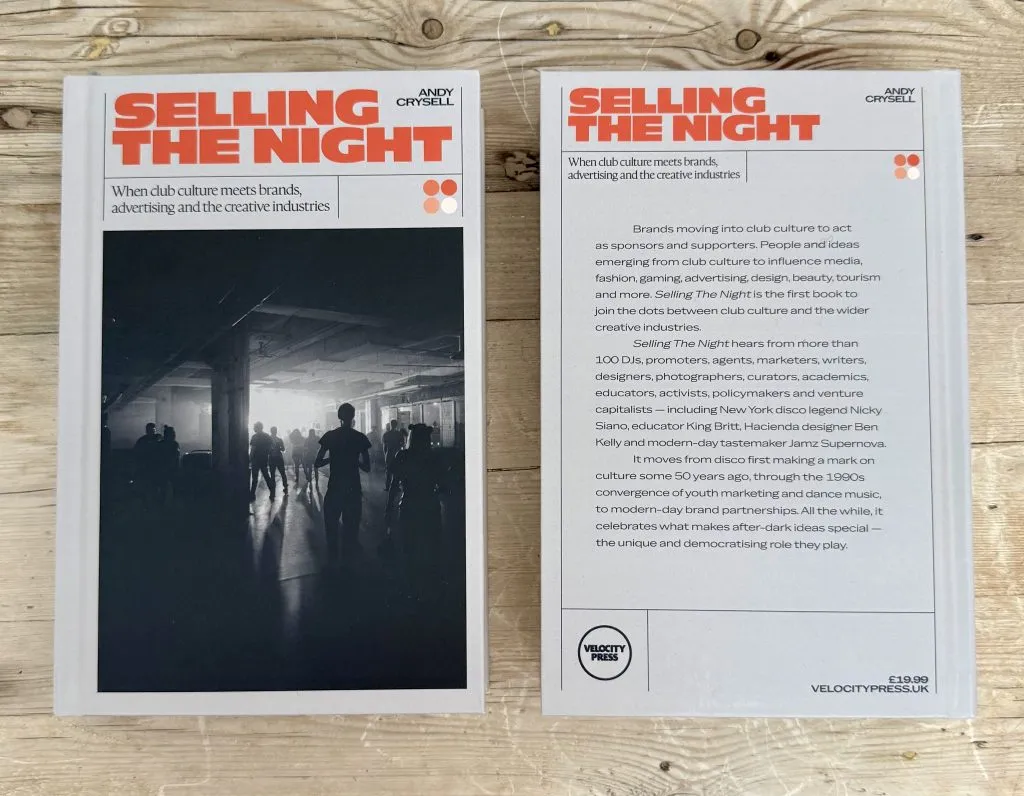

For Selling The Night (Andy’s third book, having wrote Crowd’s How We Work With Culture and also co-authored one about Ibiza way back in the 1990s), he spent last year interviewing more than 100 DJs, promoters, marketers, academics, activists, archivists, policymakers, photographers, writers and designers, urban planners and venture capitalists – and reading countless more stuff – to bring together a forensic portrait of both how brands stake a space on the dancefloor, and how club culture takes a place in the wider creative industries.

“I can’t say it was a bigger challenge than running an agency…” Crowd DNA Founder Andy Crysell talks about Selling the Night, his book about club culture and brands…

The book begins with KFC putting DJ Colonel Sanders on stage at Miami’s Ultra Music Festival in 2019 (“the bottom of the barrel”) but as he tells Crowd’s EMEA Managing Director, Joey Zeelen, the story leads to brighter moments, often through asking questions like: “Can brands ever show up in a way that brings something meaningful to the subculture? Can they be additive rather than extractive?” But mainly because it tells some fantastic stories of not just selling the dancefloor, but the best moments on them.

We couldn’t wait to hear more…

How did running Crowd for over 15 years (Andy left the business at the end of 2023) feed into this book?

I guess I can claim to have had a foot in both camps: a contributor and a participant in the music subculture, including writing about it as a journalist. But then over 20 years spent running two agencies and seeing the other side, working with a bunch of brands wrestling with things like, ‘how do you show up in culture?’ The eternal struggle for ‘authenticity’. I’m probably in a small camp of people who could write the book from this kind of rounded perspective.

What is your view on how brands should show up in culture – and how has it evolved?

Going into a project like this, I suppose you are vaguely hopeful you’re going to crack some magic formula through the research and interviews, but you kind of know you’re not. I don’t think there is any secret formula to it. But there are some basics to consider, like consistency trumps short-termism; the value of staying in your lane in terms of having a clear idea what your role in the culture is; and actually collaborating meaningfully with the community on what that role should be. The last of these is no doubt pretty obvious to anyone working in cultural insight, but seemingly not so across businesses as a whole. It’s amazing how hard they still find doing that.

And I think a simplified way to think about how things have evolved is we’ve gone through stages where, firstly, brands didn’t do much more than put up their banners and posters; to then trying to enhance what was going on, either through creating content to document the culture or experiences at the events which otherwise wouldn’t be possible; and now there’s a language shift to talking about grants and funds rather than marketing initiatives – as in brands implying they will support the infrastructure of club culture more deeply and over a prolonged time.

Of course, some people very reasonably don’t think brand money should be anywhere near club culture. I get that, but dance music is also a pretty broad church these days. I’m probably boringly in the middle on this one. You know, I’m not super pro, I’m not super anti brands in culture. I’m pragmatic that culture and creativity needs money from somewhere. It can come from within the community itself, which is amazing when it works. It can come from arts-type funding. Feasibly it can come from institutional investors. Or it can of course come from brands. Something I found positive with many of the people I spoke to for the book is they’re thinking up clever ways to combine these sources of money. Therefore, brand money in the mix, but not being totally reliant on it.

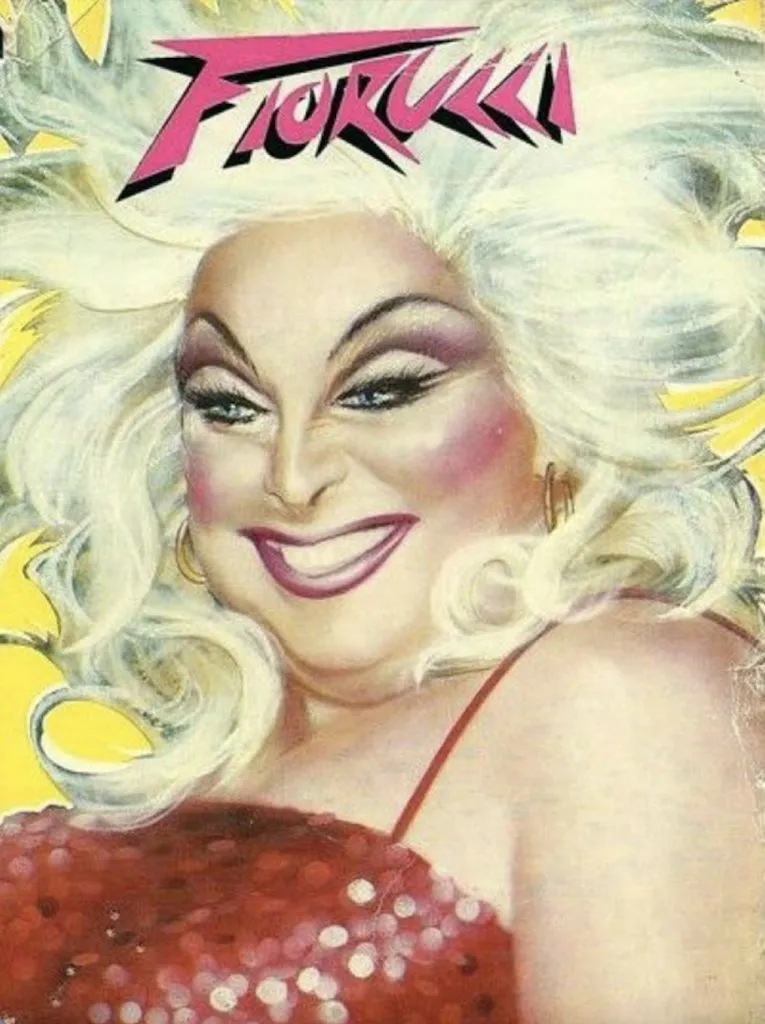

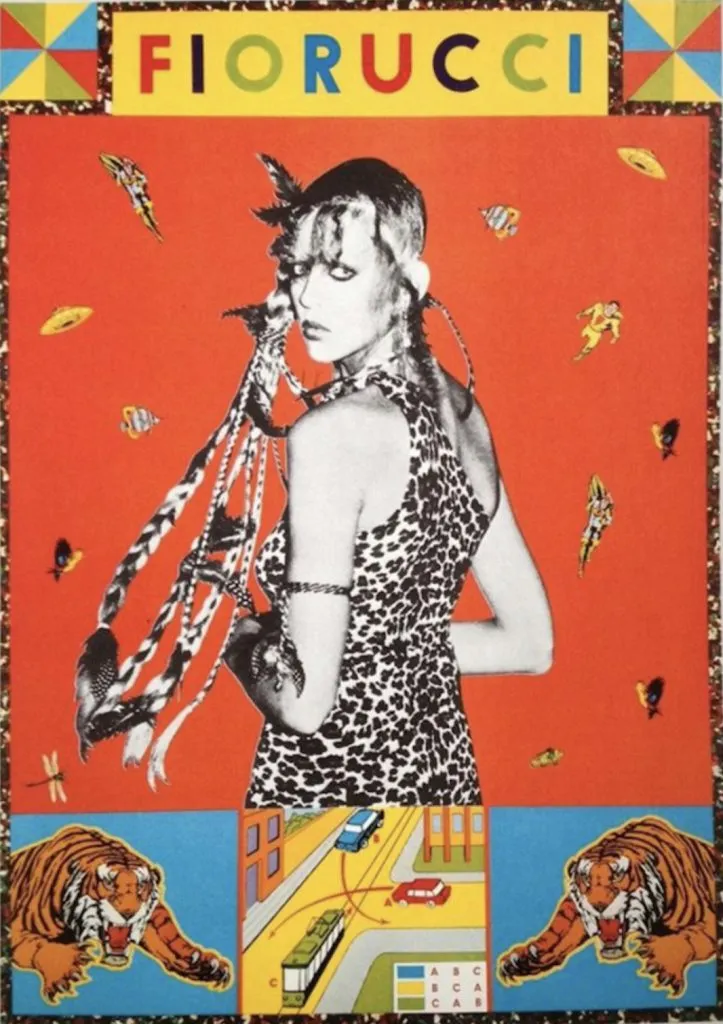

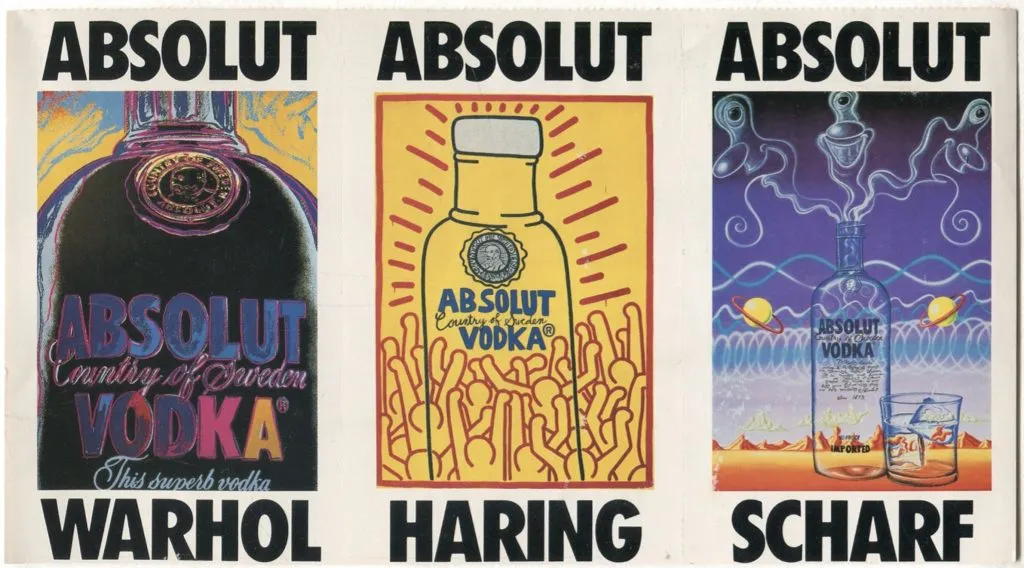

Campaigns from Fiorucci’s disco years, including singer and drag queen Divine. Meanwhile, NYC clubbers would plaster the walls of their loft spaces and walk ups with Absolut vodka adverts by artists like Andy Warhol, Keith Waring (above) and Kenny Scharf.

A big theme through the book is how dance music, whether disco or rave or through related organisations like Red Mull Music Academy, have given wider access to the creative industries…

Yeah, I’ve always felt dance music and club culture has had this democratising power, creating opportunities and pathways for those who may otherwise not have had them – including those from working class backgrounds and marginalised communities. But I was also curious if that still felt the case, in a more gentrified world where operating without a safety net of privilege is so much harder. In a more polarised world, where you have big dance music festivals and venture capital-backed Drumsheds-style things on the one side. Very underground, community-minded parties for-those-in-the-know on the other. Most things in the middle (Fabric an exception as it’s still going, but spaces of that kind), struggling to survive. What I heard, to paraphrase, is that it can still work like that, but you have to be more organised than was once the case. You can’t leave things to change and assume one thing will automatically lead to another.

But the potential is still there. There’s something about club, rave, dance culture, whatever you want to call it, which puts you in closer proximity to the heart of it all. It is intrinsically participatory. You contribute to it, add to it, even if you’re not necessarily putting on the night. Bit of a generalisation, but I’m not sure that rock music, for instance, offers that. This sense of the creativity being relatable and within reach, and of joining cultural dots. I think there’s something in that in how dance music has created opportunities for people.

So many people I spoke to for the book talked passionately about the impact that club culture has had on their careers in creative fields. Even if their career ultimately now doesn’t have a lot to do with club culture, they can draw those through lines.

You mentioned how club culture is needing to get more organised?

It was one of the loudest messages I heard in the course of writing the book. It feels like people are just getting more and more armed with information really. And community now means more than it ever did in dance music. It’s a term that’s always been used but I think for many it didn’t mean much more than the like minded people I go dancing with. Whereas now there’s much more intentionality to it – I suppose this sense that if you can’t trust the outside world, you look inwards for support and solutions.

And I was also amazed at how much I heard people talk about education. You know, I don’t think I would ever have heard the word education and dance music in the same sentence in the past. Now everyone is looking into their communities to learn about everything from how you get funding, to how you organise a night, to how you make DJing more accessible, to how you resurface origin stories and so on.

And I guess it’s about a reaction to a tougher world, really, isn’t it? Everyone over the age of about 40 that I interviewed had this sense that things just kind of happened a bit magically – one minute you’re starting a club night or designing flyers or whatever, the next you’re making connections in the creative industries. Now you can’t leave things to chance…

Electronic Beats parties, sponsored by Deutsche Telekom, Electronic Beats was created under the mandate of “sharing freshly gained knowledge with the community and forging new connections,” and included parties, podcasts, DVD and YouTube series.

One of the things you write about in the book is the gentrification of dance music itself, the intellectualism and also festivalisation of it. The fact there are exhibitions and tangential experiences beyond the dancefloor itself. Does this create opportunities for brands?

I think so. These tangential things seem a good fit, and places where brands can feel additive rather than extractive. I think this takes us back to the Red Bull Music Academy example. They did put on parties but they were better known for what they did in terms of documenting the culture, telling stories that weren’t getting told and sharing knowledge. They did it for 21 years as well, which goes a long way in terms of building trust. It’s easy to see why that kind of thing is a better fit for brands than trying to have a presence in a sweaty basement club where there’s 100 people, a DJ hiding in the corner, a strobe light, big speakers and not much else needed.

Talk to us about metrics, how you measure the value of brands working with cultures like dance music?

Short-termism came up a lot in conversations as a problem, in terms of brands getting involved in dance music – and then just as swiftly uninvolved. There’s lots of reasons for this; not least CMOs tending to leave their roles after about two years and not wanting to waste energy on longer term initiatives that they won’t get the credit for. But also a sense that initiatives in music often fail because brand and agency people can’t quite prove the success of them. They’ve got to go upstairs and there’s someone there that doesn’t give a shit about underground culture. For them, it’s just another marketing outlay and they’re not seeing the evidence around success and efficacy that they see from more conventional advertising, where the forms of measurement are well established.

What can help here?

Well, someone could put more effort into creating the metrics, the KPIs – perhaps a research agency could help with that. But I guess more broadly, people brand and agency-side need to learn to speak fluently in two languages: to be able to speak credibly to people within the culture but also explain the commercial benefits to those in the corporation. You need to have a game plan, don’t you? How do you deal with your people upstairs? How do you create that space around what you’re doing that means you’re not being measured by the quarter? How do you create a bit of room? A ‘moat’, I suppose you could describe it. That gives you the space to go further, and be more adventurous in what you do. And having a really strong team that absolutely believes in it all a little bit more than it just being their day job.

You also spoke to people focused on how cities operate after dark – what did you hear from them?

I learned that there are a lot of people in cities around the world trying to cook up new ways that club culture can thrive. Different types of multi-purpose arts space emerging beyond the conventional nightclub. Different types of relationship forming with the authorities in each city.

For instance, I spoke to Lutz Leichsenring, who runs the ClubCommission in Berlin. He was very enthusiastic about a future of people coming back into the centre of cities for creativity and cultural experiences. He was arguing that people aren’t working or shopping in the centre of cities anymore, so an after dark purpose becomes more of an imperative for those who plan urban futures.

And within all of this, there seems to be this overdue but growing realisation of how much we’ve lost by prioritising our digital lives over the time we spend in person with others. You know, that something we used to think of as just our normal lives now has a weird little name attached to it: IRL. I don’t think club culture will look the same as it did, but I’m sure with this in mind it will flourish in new forms.

Sometimes what I see in the night from brands is just so obvious – and kind of boring – any tips?

I mean, I think it’s sort of testament to the time we’re in that people probably don’t feel that brave. Probably people do feel scared about committing too much, and that everything needs to be very, very measurable. That said, I do think there are brands doing interesting things, whether it’s contributing to shining a light on sub-Saharan dance music, creating platforms for women DJs, funding mobile studios, or helping venues to train their staff to deal with sexual harassment. It’s not on the scale of RBMA, but in the best cases it’s well designed and supportive.

I guess there’s probably some responsibility on the dance music side, too – to be more directive and proactive in what brand input they do and don’t want, and to design ideas and approaches together.

Sometimes what I see in the night from brands is just so obvious – and kind of boring – any tips?

Cop-out answer but everyone was great. And I really did appreciate everyone being generous with their time and opinions. I loved going to interview DJ Nicky Siano, who took me back to the earliest days, to pre-disco and Stonewall era NYC. He was telling me about hanging outside the gay bars when he was 14 years old: he wasn’t allowed to go in, but it was to hear the music playing inside. There was just a lot of richness in that story.

Jamz Supernova was so interesting too – she has such an impressively clear perspective on what’s changing globally and how conventions are being challenged. It was all so positive to hear. King Britt as well – I have a lot of admiration for his Blacktronika initiative in San Diego, deepening understanding of how people of colour have shaped electronic music.

And also Torsten Schmidt (co-found of Yadastar, who developed the Red Bull Music Academy), partly because of the process, because he wasn’t responding to my emails at all. Then he was giving me these really strange, cryptic responses. And then he agreed to be interviewed, but it had to be when he was walking the dog for some reason. After all of that, he was really open and forthcoming on the RBMA story and the intentions behind it.

Sometimes what I see in the night from brands is just so obvious – and kind of boring – any tips?

Yes, there’s that crazy statistic that there’s now more access to law and finance than the creative industries – which sounds ridiculous. I’d love to see more agencies doing stuff that feels a bit more now, and real, rather than just self-congratulatory, on paper, and that doesn’t necessarily have any tangible impact. It feels like there’s a lot of showboating from the various trade organisations like MRS, too. Also a strong sense that this is just about doing people a favour rather than it being an absolute necessity to increase access to these industries to have fresh ideas, exciting thinking and better perspectives.

I have occasional rants on LinkedIn about job ads saying a degree is required. It feels absurdly exclusionary to me – ploddy stuff from ploddy companies. I’ve had a reasonable success rate so far. I’m tracking at six companies that have changed their ads to two that have refused. It’s interesting hearing their reasons and excuses, too.

What’s next? Finally, some rest?

Good question. No good answer – still to be worked out! Post-Crowd, there’s been a lot of wide open spaces and that’s been interesting for me. I’ve got another book coming up in about a month. This one’s called No Way Back and curates music and subculture journalism from the 70s and 80s. We’re exploring where we could take No Way Back as a brand, beyond this first release. I also have some more ideas for books taking shape. I’m working with Museum Of Youth Culture on how they partner with brands and broadcasters. And, just maybe, I have interests in starting another business. Not in the insight space. Branded content, as horrible a term as it is, is interesting to me. New ways to present and monetise editorial and create IP. I think there’s more value in these stories about humans and culture than ever. We just need to get more inventive in how we do this.

To buy a copy of Selling The Night go here.